Difference between revisions of "Boom Construction Competition"

| (114 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=Objective= | ==Objective== | ||

The | The objective of this lab is to design and assemble a boom. The performance of the boom will be judged by a design equation that includes boom mass, boom length, mass held, and anchor time. The team with the highest equation result will win the competition. | ||

=Overview= | ==Overview== | ||

A <b>boom</b> is used to lift and move heavy | A <b>boom</b> is a device used to lift and move heavy objects that are heavier than the boom itself. Booms can be found everywhere in society, particularly in construction; cantilever bridges and cranes, for example, are common examples of booms. | ||

A common example of a boom is a cantilever bridge, which uses two booms extending from a common base (Figure 1). | |||

[[Image:Lab_boom_13.png|650px|thumb|center|Figure 1: A Cable-Stayed (Cantilever) Bridge]] | [[Image:Lab_boom_13.png|650px|thumb|center|Figure 1: A Cable-Stayed (Cantilever) Bridge]] | ||

| Line 15: | Line 13: | ||

The Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge is a double cantilever bridge (Figure 2). It has two bases with two booms extending from each base and the cantilevers placed end to end. | The Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge is a double cantilever bridge (Figure 2). It has two bases with two booms extending from each base and the cantilevers placed end to end. | ||

[[Image:lab_boom_10.jpg|frame|center|Figure 2: Ed | [[Image:lab_boom_10.jpg|frame|center|Figure 2: Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge]] | ||

The Grand Bridge over Newtown Creek is a swing bridge, also known as a rotating bridge (Figure 3). This bridge has two booms mounted on a base that rotates. | The Grand Bridge over Newtown Creek is a swing bridge, also known as a rotating bridge (Figure 3). This bridge has two booms mounted on a base that rotates. | ||

[[Image:lab_boom_11.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 3: Grand Bridge | [[Image:lab_boom_11.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 3: Grand Bridge]] | ||

Figure 4 shows a bascule bridge, more commonly known as a drawbridge | Figure 4 shows a bascule bridge, more commonly known as a drawbridge. This bridge uses a big, flat boom. | ||

[[Image:lab_boom_12.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 4: Bascule Bridge]] | [[Image:lab_boom_12.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 4: Bascule Bridge]] | ||

Cranes are | Cranes are another common example of booms. The crane pictured in Figure 5 is a tower crane. These cranes are a fixture on construction sites around the world. A tower crane can lift a 40,000 lb load. It is attached to the ground by anchor bolts driven through a 400,000 lb concrete pad poured a few weeks before the crane is erected (Howstuffworks.com, 2003). | ||

[[Image:Tower Crane.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 5: A Tower Crane (Jennings, 2015)]] | [[Image:Tower Crane.jpg|650px|thumb|center|Figure 5: A Tower Crane (Jennings, 2015)]] | ||

== Stress and Strain == | === Stress and Strain === | ||

The design of a boom must consider the properties of the materials used to build the boom | Distributing the load being lifted over the length of the boom is the main challenge in boom design. The design must consider the maximum load the boom will be required to lift, how high the load will be lifted, and whether the boom will be moved or remain stationary while loaded. The design of a boom must also consider the properties of the materials used to build the boom. | ||

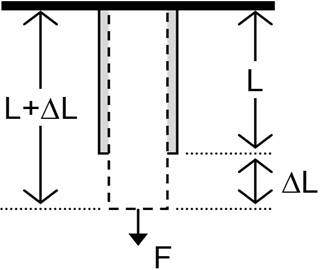

When an external force is applied to a material, it changes shape (e.g. changes length and cross-section perpendicular to the length). Understanding how deformation will affect materials is a critical consideration in boom design. The mechanical properties and deformation of solids are explained by stress and strain (Serway and Beichner, 2000). '''Stress''' is the external force acting on an object per cross sectional area. '''Strain''' is the measure of deformation resulting from an applied stress (Figure 6). | |||

[[Image:lab_boom_1.jpg|frame|center|Figure 6: Material Under Tension]] | [[Image:lab_boom_1.jpg|frame|center|Figure 6: Material Under Tension]] | ||

Tensile stress, σ, is the relationship between an applied force, ''F'', and the cross-sectional area, ''A'' (1). | |||

<center><math>\sigma = \frac{F}{A}\,</math></center> | <center><math>\sigma = \frac{F}{A}\,</math></center> | ||

<p style="text-align:right">(1)</p> | <p style="text-align:right">(1)</p> | ||

The resulting strain (2) is calculated by dividing the change in length of the material by the original length. This equation finds the strain for a rod of a material. In (2), ΔL is the change in length and L<sub>0</sub> is the rod's original length. | |||

<center><math>\varepsilon = \frac{\Delta L}{L_{\text{0}}}\,</math></center> | <center><math>\varepsilon = \frac{\Delta L}{L_{\text{0}}}\,</math></center> | ||

<p style="text-align:right">(2)</p> | <p style="text-align:right">(2)</p> | ||

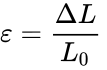

There are three basic types of stresses; <b>tensile</b> (pulling or stretching), <b>compressive</b> (squeezing or squashing), and <b>shear</b> (bending or cleaving). Consider a straight metal beam. If a <b>tensile stress</b> is applied to both ends of the beam, the length of the beam will increase, while the cross-sectional area of the beam perpendicular to the force applied will decrease. Under <b>compressive stress</b>, the opposite will occur. If the beam is subjected to <b>shear stress</b>, it will bend towards the direction of the applied force, and both the length and cross-sectional area of the beam will become distorted. Figure 7 depicts a graphic representation of the three common forms of stress. | |||

There are three basic types of stresses; tensile (pulling or stretching), compressive (squeezing or squashing), and shear (bending or cleaving). If a | |||

[[Image:Lab_boom_7.gif| | [[Image:Lab_boom_7.gif|thumb|400px|center|Figure 7: Example of a Boom Under Three Common Modes of Stress]] | ||

Strain is proportional to stress for | Strain is proportional to stress for material dependent values of strain. If the material is known, it is possible to derive strain from measured stress, and vice-versa, up to a certain level of stress. This proportionality constant is referred to as the <b>elastic modulus</b>, or '''Young’s modulus'''. The moduli of different materials is an important factor to consider when designing or building any form of structure that will be under stress. | ||

== Stress-Strain Curve == | === Stress-Strain Curve === | ||

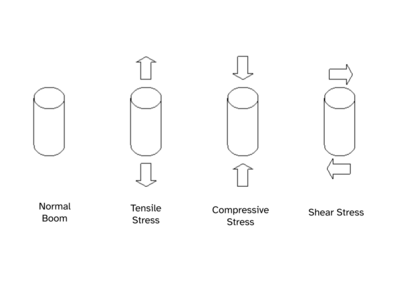

A <b>stress-strain | A graph of <b>stress-strain</b> shows the relationship between the stress and strain of a material under load. Figure 8 shows the stress-strain curve of a common metallic building material. In the <b>elastic region</b>, the material will regain its original shape once the stress is removed. The elastic region in Figure 8 is fairly linear. The slope of this linear portion of the stress-strain curve is the elastic modulus. | ||

[[Image:lab_boom_2.jpg|frame|center|Figure 8: Stress-Strain Curve of a Material Under Tension]] | [[Image:lab_boom_2.jpg|frame|center|Figure 8: Stress-Strain Curve of a Material Under Tension]] | ||

The <b>elastic limit</b> for a material is the maximum strain it can sustain before it becomes permanently deformed (i.e. if the stress is decreased, the object no longer returns to its original size and shape). | The <b>elastic limit</b> for a material is the maximum strain it can sustain before it becomes permanently deformed (i.e. if the stress is decreased, the object no longer returns to its original size and shape). In the <b>plastic region</b>, the material loses its elasticity and is permanently deformed. A linear approximation with the elastic modulus is no longer accurate. | ||

The <b>ultimate tensile strength</b> is the maximum stress a material can undergo. The <b>fracture stress</b> is the point at which the material breaks. Fracture stress is lower than the ultimate tensile strength of a material because the material has reached that level of stress and has already begun to fail. The cross-sectional area is constantly decreasing until the material finally breaks. | |||

the | |||

In addition to these intrinsic materials factors, the behavior of materials as they age and are used in service must be considered in boom design. These factors are not applicable to the boom design in this lab, but they must be considered when deciding what material to use for a design. The loss of desirable properties through use, called <b>fatigue</b>, is important. Non-static loads, repeated loading and unloading, or loads that include vibrations or oscillations will eventually lead to failure in service. Special care must be taken with live loads and situations where small motions may be magnified by design features. | |||

There are many factors to consider in any design project. When designing and constructing the boom for this competition, consider the materials being used and what might cause those materials to fail under a load. | |||

==Competition Rules== | |||

The following rules must be followed to qualify for the competition. | |||

The | |||

Violation of any of these rules will result in the disqualification of the | Violation of any of these rules will result in the disqualification of the | ||

design. | design. | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li>The boom | <li>The boom must be anchored to the white plastic anchorage provided at the front of the lab | ||

<li>The boom must extend at least 1.5 | <li>The boom mass ratio must be greater than 1 | ||

the anchorage< | <li> The dowels must be used as-is; they cannot be cut further | ||

<li>The boom must be anchored in | <li>The boom must extend at least 1.5 m horizontally from the front edge of | ||

the anchorage for the entire run | |||

<li> The boom must start at least 0.30 m from the ground after adding 15 grams of preload | |||

<li>The boom must be anchored in 2 min or less</li> | |||

<li>The boom may not touch anything but the anchorage</li> | <li>The boom may not touch anything but the anchorage</li> | ||

<li>The < | <li>The boom’s performance will be assessed by its anchor time, boom mass, boom length, and the mass it can support before deflecting 0.20 m vertically</li> | ||

<li> A team can use any number of dowels, as long as their total length is less than or equal to the length of 4 uncut dowels (4 x 122 cm, or 488 cm) | |||

</ul> | |||

The '''basic mass ratio''' (3) is defined via the mass supported in grams divided by the boom mass in grams. | |||

<center><math> | <center><math>Mass\ Ratio = \frac{Mass\ Supported\left[\text{g}\right]}{Boom\ Mass\left[\text{g}\right]}\,</math></center> | ||

<p style="text-align:right">(3)</p> | <p style="text-align:right">(3)</p> | ||

The winning design will be determined by the competition equation (4) which includes the mass ratio, anchor time in seconds, and boom length in meters. | |||

<center><math> | <center><math>Competition\ Equation = (Mass\ Ratio)^2 \times \frac{60\left[\text{s}\right]}{Anchor\ Time\left[\text{s}\right]+30\left[\text{s}\right]} \times \frac{Boom\ Length\left[\text{m}\right]}{1.5\left[\text{m}\right]}\,</math></center> | ||

<p style="text-align:right">(4)</p> | <p style="text-align:right">(4)</p> | ||

=Design Considerations= | ==Design Considerations== | ||

* How can the boom be built and/or reinforced to prevent as much deflection as possible? | * How can the boom be built and/or reinforced to prevent as much deflection as possible? | ||

* In which instances should you use the thin vs thick dowels? | |||

* What design aspects will maximize and minimize the design equation result? | |||

=Materials and Equipment= | ==Materials and Equipment== | ||

The following materials are available to construct the boom. | |||

*Thick dowels (122.00 cm, 81.20 cm, 61.00 cm, 40.60 cm long × 1.10 cm diameter) | |||

*Thin dowels (122.00 cm, 81.20 cm, 61.00 cm, 40.60 cm long × 0.80 cm diameter) | |||

*3D printed dowel adaptors | |||

*Cellophane tape | |||

*String | |||

< | <!--{| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ Table 1: Materials Available for Boom Construction | |||

!Item Name!!!!Dimensions!!!!Quantity | |||

|- | |||

|Dowel Length || || Dowel Diameter || || | |||

|- | |||

|Full Length || 122 cm || Thick || 1.1 cm || | |||

|- | |||

| || || Thin || 0.8 cm || | |||

|- | |||

|2/3 Length || 81.2 cm || Thick || 1.1 cm || | |||

|- | |||

| || || Thin || 0.8 cm || | |||

|- | |||

|1/2 Length || 61 cm || Thick || 1.1 cm || | |||

|- | |||

| || || Thin || 0.8 cm || | |||

|- | |||

|1/3 Length || 40.6 cm || Thick || 1.1 cm || | |||

|- | |||

| || || Thin || 0.8 cm || | |||

|- | |||

|3D Printed Dowel Adaptors || || || || Unlimited | |||

|- | |||

|Cellophane Tape || || || || Unlimited | |||

|- | |||

|String || || || || Unlimited | |||

|}--> | |||

== Procedure == | |||

=== Part 1. Boom Design and Construction === | |||

# Assess the materials and consider the design options, keeping in mind the competition specifications. Preliminary sketches must be completed during this process. | |||

# Sketch the basic design in pencil using the lab notes paper provided by a TA. Label the design clearly and have a TA sign and date it. | |||

# Construct the boom based on the completed sketch and the available materials. A TA will provide the materials allowed for the design. If the design is modified during the construction phase, make sure to note the changes and describe the reasons for them. | |||

# Since anchor space is limited, each boom is only allowed to use an anchor for '''10 min''' at a time. The TAs will keep track of the time, and booms will rotate every 10 min to ensure that every boom has access to an anchor. During the downtime, continue working on the boom to make the best use of the next anchoring opportunity. | |||

=== Part 2. Competition === | |||

<p><b>Note: </b | <p><b>Note: </b>Attaching the boom to the anchorage is a critical phase of the competition. Anchoring will be timed. Making a plan to anchor the boom quickly will improve its standing in the competition. Practice anchoring before the trial begins. The boom will be disqualified if anchoring the boom takes more than 2 min. | ||

anchorage is a critical phase of the competition. | |||

improve | |||

trial begins. | |||

more than | |||

# When the TA says "Go," attach the boom to the anchorage and shout "Done" when the boom is anchored. The TA will only stop the timer once all hands are off the boom. The TA will give the anchoring time that will be used to compute the boom's design ratio. | |||

# A TA will measure the horizontal length of the boom and record the length in the competition spreadsheet for the section. The boom must remain past the 1.50 m mark throughout the whole run in order to be an accepted run. | |||

# A TA will attach a basket to the end of the boom and add weights until the boom deflects (bends) 0.20 m vertically. The load will be weighed on the lab scale and recorded in the competition spreadsheet for the section. | |||

# Calculate the mass with [[Media: Lab 4 Student Sheet.xlsx|this sheet]] by filling out the required values colored in gray. Students can also chose to calculate a preliminary mass ratio and competition result by filling out the sheet. | |||

# The design ratio for the boom design will be used to decide the winner of the competition. | |||

< | <p>A TA will prepare an Excel file with the section's results and upload it to the the [http://eg.poly.edu/documents.php Lab Documents] section of the EG1004 website. | ||

==Assignment== | |||

=== Individual Lab Report === | |||

* What factors were considered in designing the boom? Discuss the background information that was used | |||

* Describe the competition rules, the ratio, and materials in the Introduction. What impact did the rules, the materials and ratio have on any design decisions? | |||

* Describe the function of each component used in the design | |||

* Describe the advantages and disadvantages of the boom design | |||

* Discuss potential design improvements. How can the design be optimized (i.e. improve the design ratio) using the experience gained from this lab? | |||

* Which elements of the boom were stressed by the load? Did the load deflect to the side, and if so, did that contribute to the boom failing? Describe the load’s direction and how the load contributed to the failure? | |||

* Include the Excel spreadsheet with all the boom designs in the class. Discuss other designs in the class | |||

* Contribution Statement | |||

===Team PowerPoint Presentation=== | |||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

<li> | <li>How can the boom design be improved?</li> | ||

<li>Other than the examples given in this lab, what are other boom examples in the real world?</li> | |||

<li>Which elements of the boom (e.g., wooden dowels, 3D printed dowel connectors, string, etc.,) were stressed by the load, in what directions, and could potentially lead to the failure? | |||

<li> | |||

<li>Which elements of the boom (e.g., wooden dowels, 3D printed dowel connectors, | |||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

== References == | |||

< | <i>How Stuff Works</i> website. 2003. SHW Media Network. Retrieved July 28, 2003. | ||

http://science.howstuffworks.com/tower-crane3.htm | |||

Jennings, James. 2015. “Up, UP in a Crane: What Life is Like as a Tower Crane Operator.” Philadelphia. Accessed 14 January 2020 from www.phillymag.com | |||

Serway, R., Beichner, R., <i>Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, 5</i><i><sup>th</sup></i> Edition. Fort Worth, TX: Saunders College Publishing, 2000 | |||

{{Laboratory Experiments}} | |||

Latest revision as of 15:12, 4 October 2024

Objective

The objective of this lab is to design and assemble a boom. The performance of the boom will be judged by a design equation that includes boom mass, boom length, mass held, and anchor time. The team with the highest equation result will win the competition.

Overview

A boom is a device used to lift and move heavy objects that are heavier than the boom itself. Booms can be found everywhere in society, particularly in construction; cantilever bridges and cranes, for example, are common examples of booms.

A common example of a boom is a cantilever bridge, which uses two booms extending from a common base (Figure 1).

The Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge is a double cantilever bridge (Figure 2). It has two bases with two booms extending from each base and the cantilevers placed end to end.

The Grand Bridge over Newtown Creek is a swing bridge, also known as a rotating bridge (Figure 3). This bridge has two booms mounted on a base that rotates.

Figure 4 shows a bascule bridge, more commonly known as a drawbridge. This bridge uses a big, flat boom.

Cranes are another common example of booms. The crane pictured in Figure 5 is a tower crane. These cranes are a fixture on construction sites around the world. A tower crane can lift a 40,000 lb load. It is attached to the ground by anchor bolts driven through a 400,000 lb concrete pad poured a few weeks before the crane is erected (Howstuffworks.com, 2003).

Stress and Strain

Distributing the load being lifted over the length of the boom is the main challenge in boom design. The design must consider the maximum load the boom will be required to lift, how high the load will be lifted, and whether the boom will be moved or remain stationary while loaded. The design of a boom must also consider the properties of the materials used to build the boom.

When an external force is applied to a material, it changes shape (e.g. changes length and cross-section perpendicular to the length). Understanding how deformation will affect materials is a critical consideration in boom design. The mechanical properties and deformation of solids are explained by stress and strain (Serway and Beichner, 2000). Stress is the external force acting on an object per cross sectional area. Strain is the measure of deformation resulting from an applied stress (Figure 6).

Tensile stress, σ, is the relationship between an applied force, F, and the cross-sectional area, A (1).

(1)

The resulting strain (2) is calculated by dividing the change in length of the material by the original length. This equation finds the strain for a rod of a material. In (2), ΔL is the change in length and L0 is the rod's original length.

(2)

There are three basic types of stresses; tensile (pulling or stretching), compressive (squeezing or squashing), and shear (bending or cleaving). Consider a straight metal beam. If a tensile stress is applied to both ends of the beam, the length of the beam will increase, while the cross-sectional area of the beam perpendicular to the force applied will decrease. Under compressive stress, the opposite will occur. If the beam is subjected to shear stress, it will bend towards the direction of the applied force, and both the length and cross-sectional area of the beam will become distorted. Figure 7 depicts a graphic representation of the three common forms of stress.

Strain is proportional to stress for material dependent values of strain. If the material is known, it is possible to derive strain from measured stress, and vice-versa, up to a certain level of stress. This proportionality constant is referred to as the elastic modulus, or Young’s modulus. The moduli of different materials is an important factor to consider when designing or building any form of structure that will be under stress.

Stress-Strain Curve

A graph of stress-strain shows the relationship between the stress and strain of a material under load. Figure 8 shows the stress-strain curve of a common metallic building material. In the elastic region, the material will regain its original shape once the stress is removed. The elastic region in Figure 8 is fairly linear. The slope of this linear portion of the stress-strain curve is the elastic modulus.

The elastic limit for a material is the maximum strain it can sustain before it becomes permanently deformed (i.e. if the stress is decreased, the object no longer returns to its original size and shape). In the plastic region, the material loses its elasticity and is permanently deformed. A linear approximation with the elastic modulus is no longer accurate.

The ultimate tensile strength is the maximum stress a material can undergo. The fracture stress is the point at which the material breaks. Fracture stress is lower than the ultimate tensile strength of a material because the material has reached that level of stress and has already begun to fail. The cross-sectional area is constantly decreasing until the material finally breaks.

In addition to these intrinsic materials factors, the behavior of materials as they age and are used in service must be considered in boom design. These factors are not applicable to the boom design in this lab, but they must be considered when deciding what material to use for a design. The loss of desirable properties through use, called fatigue, is important. Non-static loads, repeated loading and unloading, or loads that include vibrations or oscillations will eventually lead to failure in service. Special care must be taken with live loads and situations where small motions may be magnified by design features.

There are many factors to consider in any design project. When designing and constructing the boom for this competition, consider the materials being used and what might cause those materials to fail under a load.

Competition Rules

The following rules must be followed to qualify for the competition. Violation of any of these rules will result in the disqualification of the design.

- The boom must be anchored to the white plastic anchorage provided at the front of the lab

- The boom mass ratio must be greater than 1

- The dowels must be used as-is; they cannot be cut further

- The boom must extend at least 1.5 m horizontally from the front edge of the anchorage for the entire run

- The boom must start at least 0.30 m from the ground after adding 15 grams of preload

- The boom must be anchored in 2 min or less

- The boom may not touch anything but the anchorage

- The boom’s performance will be assessed by its anchor time, boom mass, boom length, and the mass it can support before deflecting 0.20 m vertically

- A team can use any number of dowels, as long as their total length is less than or equal to the length of 4 uncut dowels (4 x 122 cm, or 488 cm)

The basic mass ratio (3) is defined via the mass supported in grams divided by the boom mass in grams.

(3)

The winning design will be determined by the competition equation (4) which includes the mass ratio, anchor time in seconds, and boom length in meters.

(4)

Design Considerations

- How can the boom be built and/or reinforced to prevent as much deflection as possible?

- In which instances should you use the thin vs thick dowels?

- What design aspects will maximize and minimize the design equation result?

Materials and Equipment

The following materials are available to construct the boom.

- Thick dowels (122.00 cm, 81.20 cm, 61.00 cm, 40.60 cm long × 1.10 cm diameter)

- Thin dowels (122.00 cm, 81.20 cm, 61.00 cm, 40.60 cm long × 0.80 cm diameter)

- 3D printed dowel adaptors

- Cellophane tape

- String

Procedure

Part 1. Boom Design and Construction

- Assess the materials and consider the design options, keeping in mind the competition specifications. Preliminary sketches must be completed during this process.

- Sketch the basic design in pencil using the lab notes paper provided by a TA. Label the design clearly and have a TA sign and date it.

- Construct the boom based on the completed sketch and the available materials. A TA will provide the materials allowed for the design. If the design is modified during the construction phase, make sure to note the changes and describe the reasons for them.

- Since anchor space is limited, each boom is only allowed to use an anchor for 10 min at a time. The TAs will keep track of the time, and booms will rotate every 10 min to ensure that every boom has access to an anchor. During the downtime, continue working on the boom to make the best use of the next anchoring opportunity.

Part 2. Competition

Note: Attaching the boom to the anchorage is a critical phase of the competition. Anchoring will be timed. Making a plan to anchor the boom quickly will improve its standing in the competition. Practice anchoring before the trial begins. The boom will be disqualified if anchoring the boom takes more than 2 min.

- When the TA says "Go," attach the boom to the anchorage and shout "Done" when the boom is anchored. The TA will only stop the timer once all hands are off the boom. The TA will give the anchoring time that will be used to compute the boom's design ratio.

- A TA will measure the horizontal length of the boom and record the length in the competition spreadsheet for the section. The boom must remain past the 1.50 m mark throughout the whole run in order to be an accepted run.

- A TA will attach a basket to the end of the boom and add weights until the boom deflects (bends) 0.20 m vertically. The load will be weighed on the lab scale and recorded in the competition spreadsheet for the section.

- Calculate the mass with this sheet by filling out the required values colored in gray. Students can also chose to calculate a preliminary mass ratio and competition result by filling out the sheet.

- The design ratio for the boom design will be used to decide the winner of the competition.

A TA will prepare an Excel file with the section's results and upload it to the the Lab Documents section of the EG1004 website.

Assignment

Individual Lab Report

- What factors were considered in designing the boom? Discuss the background information that was used

- Describe the competition rules, the ratio, and materials in the Introduction. What impact did the rules, the materials and ratio have on any design decisions?

- Describe the function of each component used in the design

- Describe the advantages and disadvantages of the boom design

- Discuss potential design improvements. How can the design be optimized (i.e. improve the design ratio) using the experience gained from this lab?

- Which elements of the boom were stressed by the load? Did the load deflect to the side, and if so, did that contribute to the boom failing? Describe the load’s direction and how the load contributed to the failure?

- Include the Excel spreadsheet with all the boom designs in the class. Discuss other designs in the class

- Contribution Statement

Team PowerPoint Presentation

- How can the boom design be improved?

- Other than the examples given in this lab, what are other boom examples in the real world?

- Which elements of the boom (e.g., wooden dowels, 3D printed dowel connectors, string, etc.,) were stressed by the load, in what directions, and could potentially lead to the failure?

References

How Stuff Works website. 2003. SHW Media Network. Retrieved July 28, 2003. http://science.howstuffworks.com/tower-crane3.htm

Jennings, James. 2015. “Up, UP in a Crane: What Life is Like as a Tower Crane Operator.” Philadelphia. Accessed 14 January 2020 from www.phillymag.com

Serway, R., Beichner, R., Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern Physics, 5th Edition. Fort Worth, TX: Saunders College Publishing, 2000

| ||||||||

![{\displaystyle Mass\ Ratio={\frac {Mass\ Supported\left[{\text{g}}\right]}{Boom\ Mass\left[{\text{g}}\right]}}\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/png/89ec3397683a749b3a2061aa287b203df7f10015)

![{\displaystyle Competition\ Equation=(Mass\ Ratio)^{2}\times {\frac {60\left[{\text{s}}\right]}{Anchor\ Time\left[{\text{s}}\right]+30\left[{\text{s}}\right]}}\times {\frac {Boom\ Length\left[{\text{m}}\right]}{1.5\left[{\text{m}}\right]}}\,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/png/2fbf14911b4bb4a077ad24f99011462b8a8a1bcb)